GJ HISTORY: Story of a lost Ute princess in Grand Junction

Garry Brewer

Grand Junction History Columnist

When we see people helping others during Christmas and other times of the year, we often marvel at how generous they are. They give so freely and seem to immerse themselves in the giving.

There were two such generous beings, miracles of lives well lived at the Teller Indian School of 124 students in Grand Junction. They, together with superintendent Captain Theodore Lemmon, the staff, local townspeople and local officials present on Christmas Day in 1892 were there to sing praises and honor the Savior of the World, the Christ Child.

Those special people that day were not the stars of the program, but one of the matrons of the school, Kate Aldura Richardson, and her young daughter, Edith Leroy Richardson. Kate had brought her upright piano with her to the school and that night she played all the music for the Christmas story, and Edith performed a solo.

It wasn't just that evening that made Kate and Edith miracles but the wonderful works they would accomplish in their lives and the fact they were lucky to be alive.

Kate, mother of Edith, was born near Springville, Utah, about 1858. She was the daughter of Chief Tintic and his wife, Copperfield, of the Ute Indians. At 18 months, Kate was adopted by Charles Edmund Richardson and his wife, Mary Ann Darrow Richardson of Springville.

This is the story of Kate and Edith, both lost princesses of the Ute Nation, who lived in our town of Grand Junction. They overcame the fear of the tribe that tried to kill Kate as a baby; Kate and Edith gave back to the Ute Nation with kindness and hope through teaching and nursing skills.

In the early fall of 1861 or 1862, according to the diary of Charles Edmund Richardson, his friend, Indian interpreter, Amos Warren, entered the Ute Camp near Clay Beds, around Springville. Amos noticed a group of Ute tribesmen around the body of a dead woman and an 18-month-old baby girl sitting on the body. One of the tribesmen shot an arrow into the neck of the baby. The child cried and with its tiny hands grabbed and took hold of the arrow. Almost immediately, another tribesman shot an arrow into the baby's leg. Amos, now standing with the circle of men around the baby, caught the arm of the next man who was about to shoot an arrow and asked: "What's going on here?"

The men told him that the toddler was the daughter of the late Chief Tintic, and his wife, the baby's mother, had died. They explained that if the baby was left to live she would inherit the Chief's wealth. Amos, thinking quickly, asked the tribe members if he could take the baby and raise her, promising never to return to claim the inheritance The tribe members let him take the baby for a horse blanket and other things amounting to about $7 or $8.

Amos removed the arrows, bound the wounds, and took the baby to Springville. Amos had many children of his own, so he asked his friends, the Richardsons, if they would take the baby in. They had one daughter and four sons, but there was room for one more. They named her Kate Aldura Richardson.

Kate was raised with the Richardson family, went to school, LDS Sunday School, and was just as much a member of the Richardson family as any natural-born child.

Kate feared the Indians would come and take her back and kill her so when any Indians came to Springville, Kate would run and hide. At times during her life, she would be seen feeling the scar on her neck from the arrow wound.

She talked often about her father, Charles Richardson, who loved to whittle. One time he whittled a small Noah's Ark, with many pairs of animals. He also whittled many dolls for Kate.

While in her early teens, Kate was once again orphaned. Her adoptive mother, Mary Ann Richardson, died in 1872; and then in 1875, Charles Edmund Richardson passed away.

Kate could not speak Ute. She had been raised in a white family and was taught the skills of life, music, singing, housekeeping, sewing, cooking, teaching, and was very religious and devout in her LDS faith.

In 1880, Kate, then 20, went to work at the home of the Lyman S. Wood family in Springville. Living next door was a boarder by the name of Charles Leroy Parrish, 30 years old and a laborer.

It seems there have always been fast-talking bad boys, and Charles Leroy Parrish was one of those. On July 13, 1881, Kate gave birth to a baby girl named Edith Leroy Richardson in Springville.

Charles had promised to marry Kate, but instead ran away and left Kate to raise her daughter alone. As was pointed out in writings of the day, Kate was betrayed by a scoundrel. That's why she did not give Edith the last name of Parrish.

Parrish ended up in California where he lived out his life, married, raised a family and died.

Kate was known for her devotion to children, so when the government provided responsible positions for staff and their children at the reservation schools, she would accept those jobs. That's how she and Edith came to live in Grand Junction.

Thanks to her education, rare privileges came to Kate and her daughter. For a number of years she was a Matron for girls at the White Rocks Indian School, then at the Teller Institute in Grand Junction until 1909, followed by the Hopi Reservation in Arizona till 1914, and then at Ft. Duchesne, Uintah County, Utah.

She was refined and attractive and particular with her personal appearance. She taught the girls in the school dormitories to live on a higher plane by strictly observing decency, cleanliness and neat appearance in dress.

In 1924, while on a visit to her hometown of Springville, Kate commented to her friend, Mrs. Georgiana Clark, "I hope I can instill into those Indian girls the inspiring teachings of our pioneer mothers."

In 1883, Kate Richardson, in an effort to recover the thousands of acres of land owned by her natural father, Chief Tintic, made an application for the lands. But the government stated in a letter that the ownership of the land in question was settled by the Ute Treaty of 1868. Kate's birthright was sold by the tribe who tried to kill her so many years before.

Kate Aldura Richardson died Dec. 29, 1927, at age 70, and is buried in Uintah County, Utah.

Kate's daughter Edith was present at her mother's death and noted that the scars on her mother's neck and leg were still visible.

Thus lived and died Kate, the princess daughter of Chief Tintic, and his wife, Copperfield, and her parents via adoption, Charles Edmund and Mary Ann Darrow Richardson.

Reaching back on that Christmas Day in 1892, at the Teller Indian Institute, the two miracles of Kate and Edith were giving to those boys and girls far from their homes, the Blessing of the Christmas Spirit.

-----------------------

Garry Brewer is storyteller of the tribe; finder of odd knowledge and uninteresting items; a bore to his grandchildren; a pain to his wife on spelling, but a locator of golden nuggets, truths and pearls of wisdom.

PHOTOS & RESEARCH SOURCES: Museum of Western Colorado, Loyd Files Room; Michael Menard; Grand Junction News; Daily Sentinel files; Snap Photo; Dean Photo; Wanda Allen; Lo Anne Curtis; Richardson Family Researcher; Krissy Giacoletto, Special Collections Department, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah; Valeri Craigle, University of Utah, Access Technologies Librarian; Teresa Tipton, Buildings and Ground, Executive Secretary, Springville, Utah; Mrs. Pearl Ross, Teller Institute History; Martha Louise Hurst, "An Indian Saga"; Floyd A. O'Neil, Interview of Edith Richardson; and Journal of the Western Slope, summer 1993, vol 8, no. 3

GJ HISTORY: Edith Leroy Richardson — An accomplished Ute Maiden of Grand Junction

January, 17 2012

GARRY BREWER

Free Press Grand Living Columnist

Each individual who researches and writes about someone from the past finds that as you read their diaries, letters, newspapers reports and comments, the long-decreased start to speak to you about their life and deeds. You hear a kind of small, quiet whisper in your heart and mind of what they want you to write and tell the current generation.

Today, I would like to share with you the life of a Ute Princess, Edith Leroy Richardson of Grand Junction, Colo. — where she was raised, things she learned, and the ideals she carried throughout her life.

It was in Grand Junction at the Park Opera House (present location of the Museum of Western Colorado between Fourth and Fifth streets on Ute Avenue) on Tuesday, May 29, 1900. The DeLong brothers, Horace T. and Ira M., had just held their oratory contest. There was a large group of students from Grand Junction High School competing that night. Awards were given to the boys, and another to the girls, for oratory and elocutionary skills.

After considerable deliberation, the first-place prize for the boys was awarded to Walter White for his speech by Patrick Henry on "Give me Liberty or Give me Death."

The first-place prize for the girls was presented to Miss Edith L. Richardson. Her oratory was declared to be the best recitation given in the city on the story of "the Sioux Chief Daughter."

As reported in the Daily Sentinel:

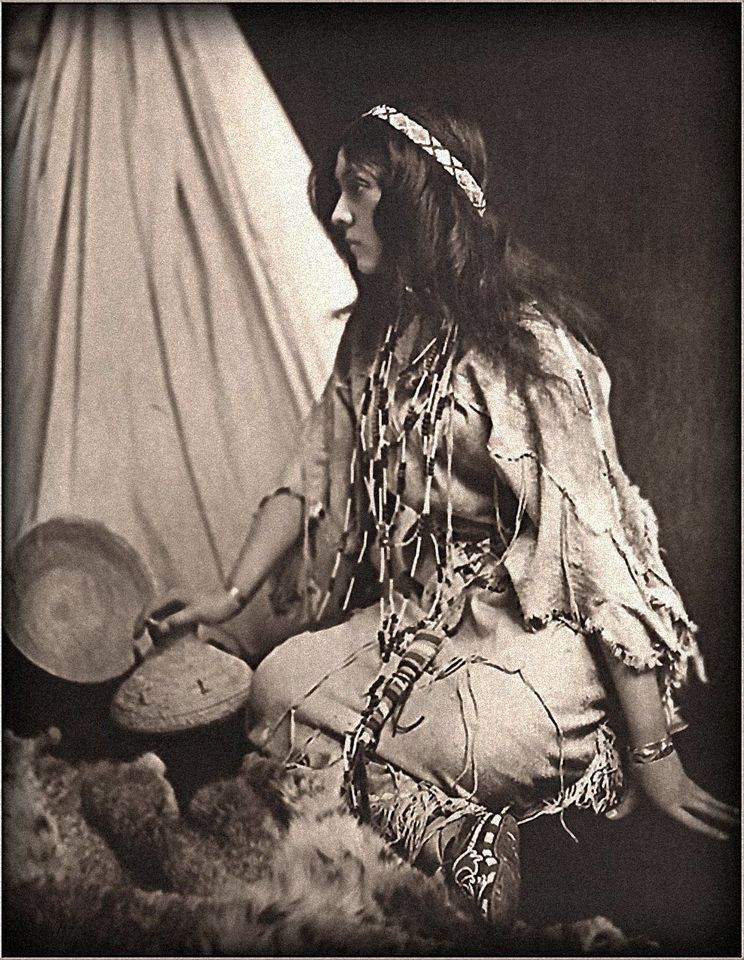

Edith was dressed in Indian costume as would befit the daughter of a chief, with her black hair hung straight and confined only by a narrow band at the head. It was said that those who had never heard her recite were surprised at her elocutionary ability. Edith held her audience spellbound from the time she came onto the stage until her recitation was finished. Every expression of her face, every motion of her body and every tone of her voice was in strict accord with the subject of her recitation.

So impressed with her presentation and costume, local photographer Frank Dean took a series of photos for a national photo contest. From this event in Grand Junction, Edith was offered many generously attractive offers to go on-stage, but she thanked all, and persisted in finishing her education before choosing a life work.

How did an Indian Princess come to live in Grand Junction, Colo.?

THE REST OF THE STORY

Edith Leroy Richardson was born July 13, 1881, in Springville, Utah, at the home of Melvin and Louella Wood Haymond. She was the daughter of Kate Aldura Richardson and Charles Leroy Parrish. During her life she was always welcome in the Haymond's home and during her working and retirement years she would return as often as she could to be with the family. Edith and the Haymond's daughter, Vera, were like sisters and remained so until death parted them in 1977.

Edith went to kindergarten in Springville; the rest of her elementary education was from private tutors on reservations where her mother's work had taken them. Her later education was in Teller Indian Institute and Grand Junction High School.

Capt. Theodore Lemmon, superintendent of the Teller Institute, would drive Edith to and from the Indian School to GJHS, then located on the corner of Sixth and Rood (present site of the Mesa County Courthouse).

A GJHS student at the time, Pearl Smith (Ross), commented that Capt. Lemmon would drive his buggy with a high-stepping team of horses to the high school. And it was his habit of walking with Edith up the long stairway of the school, buggy whip in hand.

During this time Edith was in the Indian School Mandolin & School brass band. It was said the school band was so good that the local Grand Junction Musician's Union members complained to the government that the Indian School was taking paying jobs away from them because of the free concerts given by the students.

Also, at the same time as Edith's win at the Park Opera house, some of the Teller Institute students and staff died of typhoid and Rocky Mountain fever — a problem caused by bad water and sewer systems.

Two of the students, Peter Armell, 17, and Samuel Shem, 12, were buried in the Teller Institute Cemetery. Miss Lue H. Childs, a young teacher, also passed and her brother had her body shipped home to Chicago Junction, Ohio. This may have influenced Edith to pursue a nursing career later in life.

About 1903, after high school, Edith began work as an assistant to the Rev. Milton J. Hersey of the Episcopal Church at the Uintah Reservation, Fort Duchesne, Randlett, Utah. She described the condition of the hospital at Fort Duchesne as being extremely crude, with only one hospital ward for all patients. Men, women and children were all placed in the same room, sanitation was lacking, and Henry B. Lloyd M.D. was the only doctor at the fort. The hospital was understaffed and overworked.

After serving at Fort Duchesne for a few months, Edith made up her mind to attend nursing school in Portland, Ore., where she completed her courses at Good Samaritan Hospital in 1908. From 1909 to 1920 Edith served as a private duty nurse and then went back to Fort Duchesne to work until 1922.

Edith mentioned in her diary that she had a personal acquaintance with Chipeta, wife of Chief Ouray. She told the story of Chipeta coming to Fort Duchesne, nearly blind and Edith had helped to nurse her. She describes Chipeta as warm, friendly and cultured. In about 1921, a friend of Edith's from Grand Junction, William Weiser, came and took Chipeta to St. Mary's Hospital where surgery was performed on her eyes. It should be noted that William Weiser was the nephew of William Moyer, owner of the Fair Store.

Edith worked at San Francisco General Hospital and in Eugene, Ore., from 1922-25 and updated her nursing skills with each assignment.

Kate, Edith's mother, was not in the best of health, so in 1925 Edith returned to Fort Duchesne to be near her mother, who died in 1927. Edith stayed on at Fort Duchesne until 1930 when she accepted a position at the Yakima Sanitarium for Tubercular patients in Toppenish, Wash. As a nurse there she contracted the disease and from September 1930 to February 1933 she was on compensation leave while she regained her health. After that time she moved to the Haymond home in Salt Lake City.

In 1937, with Edith's health fully regained, she left Salt Lake City for an assignment to the Klamath Agency in Oregon, then to Warm Springs, Ore., then to Ponca City, Okla., at the White Eagle Pawnee Agency, where she worked until her retirement in 1950. She then returned to Salt Lake City to be with family, and her adopted sister, Vera Haymond.

While Edith never married, she did fall in love with a doctor, Eli Abraham Kusel of Oroville, Calif. She would vacation in Oroville and those were some of the happiest times of her life. Edith's love letters from 1942 and 1943 are in her files at the University of Utah. In her papers, many times Edith repeats that the greatest mistake of her life was she did not marry Eli, and he never married either. Eli died in 1947 in California, and left Edith a diamond ring as a remembrance of his love. He also left her a $1,000.

In Edith's diary where she kept her innermost thoughts are Frank Dean photos of the Ute Maiden, Captain Theodore Lemmon, and her mother, Kate. Also in the diary are the Delong Speech contest story at the Park Opera House in 1900, her love letters to and from Eli A. Kusel, and the love for the place she grew up — Grand Junction, Colo. This was her home.

Edith was very interested in furthering the cause of women in the workforce, helping some to gain an education, and sharing her talents. She was active in the retired Government Employees association, a native member of the Utah's Art Center, and a world traveler for the Business and Professional Women' Club. She went to places like Germany, Cuba and Hawaii, attending many national meetings for the club.

Edith was passionate about promoting the standards of Indian women in education, for which she received from the Department of Interior in 1950 an honor award, and once again in 1964, an award for meritorious service to the Indian Service.

It was said that Edith was a quiet person, regal looking in her smartly tailored clothing. She was remembered by her friends as one who always had a matching hat for each outfit, and when she spoke she commanded attention for her wisdom and understanding of situations, never speaking ill of anyone.

One of her many talents was decorating banquet tables for 20 to 300 people. Many organizations called upon her for their banquets; she would always tell them, "Oh, I have the right things in my attic for your particular theme." Her skill and arrangements were breathtaking.

Just before her death, Edith had broken her hip and was in St. Joseph Villa; the ladies of the Business and Professional Women's club would visit and ask if they could pick her up and take her to the women's lunches. Edith would say: "I don't believe I can go today, but soon we may be able to go out for lunch again"

That day never came. Edith Leroy Richardson died on March 16, 1977, in Salt Lake City. She had moved on to solve "The Great Mystery" as she called it. Edith was 95 years, 8 months old. The Little Ute Princess of Grand Junction was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in the Haymond Family Lot in Springville.

EPILOGUE

So if you're on Sixth and Rood some quiet morning where the old Grand Junction High school was, and you hear the sounds of a high-stepping horse team, a snap of a horse buggy whip, footsteps of two people — it just might be Capt. Theodore Lemmon bringing the Ute Maiden, WE-TA-LE-TA, Edith Leroy Richardson to high school for her lessons.

======================

Garry Brewer is storyteller of the tribe; finder of odd knowledge and uninteresting items; a bore to his grandchildren; a pain to his wife on spelling; but a locator of golden nuggets, truths and pearls of wisdom.

GJ HISTORY: Story of a lost Ute princess in Grand Junction

Garry Brewer

Grand Junction History Columnist

When we see people helping others during Christmas and other times of the year, we often marvel at how generous they are. They give so freely and seem to immerse themselves in the giving.

There were two such generous beings, miracles of lives well lived at the Teller Indian School of 124 students in Grand Junction. They, together with superintendent Captain Theodore Lemmon, the staff, local townspeople and local officials present on Christmas Day in 1892 were there to sing praises and honor the Savior of the World, the Christ Child.

Those special people that day were not the stars of the program, but one of the matrons of the school, Kate Aldura Richardson, and her young daughter, Edith Leroy Richardson. Kate had brought her upright piano with her to the school and that night she played all the music for the Christmas story, and Edith performed a solo.

It wasn't just that evening that made Kate and Edith miracles but the wonderful works they would accomplish in their lives and the fact they were lucky to be alive.

Kate, mother of Edith, was born near Springville, Utah, about 1858. She was the daughter of Chief Tintic and his wife, Copperfield, of the Ute Indians. At 18 months, Kate was adopted by Charles Edmund Richardson and his wife, Mary Ann Darrow Richardson of Springville.

This is the story of Kate and Edith, both lost princesses of the Ute Nation, who lived in our town of Grand Junction. They overcame the fear of the tribe that tried to kill Kate as a baby; Kate and Edith gave back to the Ute Nation with kindness and hope through teaching and nursing skills.

In the early fall of 1861 or 1862, according to the diary of Charles Edmund Richardson, his friend, Indian interpreter, Amos Warren, entered the Ute Camp near Clay Beds, around Springville. Amos noticed a group of Ute tribesmen around the body of a dead woman and an 18-month-old baby girl sitting on the body. One of the tribesmen shot an arrow into the neck of the baby. The child cried and with its tiny hands grabbed and took hold of the arrow. Almost immediately, another tribesman shot an arrow into the baby's leg. Amos, now standing with the circle of men around the baby, caught the arm of the next man who was about to shoot an arrow and asked: "What's going on here?"

The men told him that the toddler was the daughter of the late Chief Tintic, and his wife, the baby's mother, had died. They explained that if the baby was left to live she would inherit the Chief's wealth. Amos, thinking quickly, asked the tribe members if he could take the baby and raise her, promising never to return to claim the inheritance The tribe members let him take the baby for a horse blanket and other things amounting to about $7 or $8.

Amos removed the arrows, bound the wounds, and took the baby to Springville. Amos had many children of his own, so he asked his friends, the Richardsons, if they would take the baby in. They had one daughter and four sons, but there was room for one more. They named her Kate Aldura Richardson.

Kate was raised with the Richardson family, went to school, LDS Sunday School, and was just as much a member of the Richardson family as any natural-born child.

Kate feared the Indians would come and take her back and kill her so when any Indians came to Springville, Kate would run and hide. At times during her life, she would be seen feeling the scar on her neck from the arrow wound.

She talked often about her father, Charles Richardson, who loved to whittle. One time he whittled a small Noah's Ark, with many pairs of animals. He also whittled many dolls for Kate.

While in her early teens, Kate was once again orphaned. Her adoptive mother, Mary Ann Richardson, died in 1872; and then in 1875, Charles Edmund Richardson passed away.

Kate could not speak Ute. She had been raised in a white family and was taught the skills of life, music, singing, housekeeping, sewing, cooking, teaching, and was very religious and devout in her LDS faith.

In 1880, Kate, then 20, went to work at the home of the Lyman S. Wood family in Springville. Living next door was a boarder by the name of Charles Leroy Parrish, 30 years old and a laborer.

It seems there have always been fast-talking bad boys, and Charles Leroy Parrish was one of those. On July 13, 1881, Kate gave birth to a baby girl named Edith Leroy Richardson in Springville.

Charles had promised to marry Kate, but instead ran away and left Kate to raise her daughter alone. As was pointed out in writings of the day, Kate was betrayed by a scoundrel. That's why she did not give Edith the last name of Parrish.

Parrish ended up in California where he lived out his life, married, raised a family and died.

Kate was known for her devotion to children, so when the government provided responsible positions for staff and their children at the reservation schools, she would accept those jobs. That's how she and Edith came to live in Grand Junction.

Thanks to her education, rare privileges came to Kate and her daughter. For a number of years she was a Matron for girls at the White Rocks Indian School, then at the Teller Institute in Grand Junction until 1909, followed by the Hopi Reservation in Arizona till 1914, and then at Ft. Duchesne, Uintah County, Utah.

She was refined and attractive and particular with her personal appearance. She taught the girls in the school dormitories to live on a higher plane by strictly observing decency, cleanliness and neat appearance in dress.

In 1924, while on a visit to her hometown of Springville, Kate commented to her friend, Mrs. Georgiana Clark, "I hope I can instill into those Indian girls the inspiring teachings of our pioneer mothers."

In 1883, Kate Richardson, in an effort to recover the thousands of acres of land owned by her natural father, Chief Tintic, made an application for the lands. But the government stated in a letter that the ownership of the land in question was settled by the Ute Treaty of 1868. Kate's birthright was sold by the tribe who tried to kill her so many years before.

Kate Aldura Richardson died Dec. 29, 1927, at age 70, and is buried in Uintah County, Utah.

Kate's daughter Edith was present at her mother's death and noted that the scars on her mother's neck and leg were still visible.

Thus lived and died Kate, the princess daughter of Chief Tintic, and his wife, Copperfield, and her parents via adoption, Charles Edmund and Mary Ann Darrow Richardson.

Reaching back on that Christmas Day in 1892, at the Teller Indian Institute, the two miracles of Kate and Edith were giving to those boys and girls far from their homes, the Blessing of the Christmas Spirit.

-----------------------

Garry Brewer is storyteller of the tribe; finder of odd knowledge and uninteresting items; a bore to his grandchildren; a pain to his wife on spelling, but a locator of golden nuggets, truths and pearls of wisdom.

PHOTOS & RESEARCH SOURCES: Museum of Western Colorado, Loyd Files Room; Michael Menard; Grand Junction News; Daily Sentinel files; Snap Photo; Dean Photo; Wanda Allen; Lo Anne Curtis; Richardson Family Researcher; Krissy Giacoletto, Special Collections Department, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah; Valeri Craigle, University of Utah, Access Technologies Librarian; Teresa Tipton, Buildings and Ground, Executive Secretary, Springville, Utah; Mrs. Pearl Ross, Teller Institute History; Martha Louise Hurst, "An Indian Saga"; Floyd A. O'Neil, Interview of Edith Richardson; and Journal of the Western Slope, summer 1993, vol 8, no. 3

GJ HISTORY: Edith Leroy Richardson — An accomplished Ute Maiden of Grand Junction

January, 17 2012

GARRY BREWER

Free Press Grand Living Columnist

Each individual who researches and writes about someone from the past finds that as you read their diaries, letters, newspapers reports and comments, the long-decreased start to speak to you about their life and deeds. You hear a kind of small, quiet whisper in your heart and mind of what they want you to write and tell the current generation.

Today, I would like to share with you the life of a Ute Princess, Edith Leroy Richardson of Grand Junction, Colo. — where she was raised, things she learned, and the ideals she carried throughout her life.

It was in Grand Junction at the Park Opera House (present location of the Museum of Western Colorado between Fourth and Fifth streets on Ute Avenue) on Tuesday, May 29, 1900. The DeLong brothers, Horace T. and Ira M., had just held their oratory contest. There was a large group of students from Grand Junction High School competing that night. Awards were given to the boys, and another to the girls, for oratory and elocutionary skills.

After considerable deliberation, the first-place prize for the boys was awarded to Walter White for his speech by Patrick Henry on "Give me Liberty or Give me Death."

The first-place prize for the girls was presented to Miss Edith L. Richardson. Her oratory was declared to be the best recitation given in the city on the story of "the Sioux Chief Daughter."

As reported in the Daily Sentinel:

Edith was dressed in Indian costume as would befit the daughter of a chief, with her black hair hung straight and confined only by a narrow band at the head. It was said that those who had never heard her recite were surprised at her elocutionary ability. Edith held her audience spellbound from the time she came onto the stage until her recitation was finished. Every expression of her face, every motion of her body and every tone of her voice was in strict accord with the subject of her recitation.

So impressed with her presentation and costume, local photographer Frank Dean took a series of photos for a national photo contest. From this event in Grand Junction, Edith was offered many generously attractive offers to go on-stage, but she thanked all, and persisted in finishing her education before choosing a life work.

How did an Indian Princess come to live in Grand Junction, Colo.?

THE REST OF THE STORY

Edith Leroy Richardson was born July 13, 1881, in Springville, Utah, at the home of Melvin and Louella Wood Haymond. She was the daughter of Kate Aldura Richardson and Charles Leroy Parrish. During her life she was always welcome in the Haymond's home and during her working and retirement years she would return as often as she could to be with the family. Edith and the Haymond's daughter, Vera, were like sisters and remained so until death parted them in 1977.

Edith went to kindergarten in Springville; the rest of her elementary education was from private tutors on reservations where her mother's work had taken them. Her later education was in Teller Indian Institute and Grand Junction High School.

Capt. Theodore Lemmon, superintendent of the Teller Institute, would drive Edith to and from the Indian School to GJHS, then located on the corner of Sixth and Rood (present site of the Mesa County Courthouse).

A GJHS student at the time, Pearl Smith (Ross), commented that Capt. Lemmon would drive his buggy with a high-stepping team of horses to the high school. And it was his habit of walking with Edith up the long stairway of the school, buggy whip in hand.

During this time Edith was in the Indian School Mandolin & School brass band. It was said the school band was so good that the local Grand Junction Musician's Union members complained to the government that the Indian School was taking paying jobs away from them because of the free concerts given by the students.

Also, at the same time as Edith's win at the Park Opera house, some of the Teller Institute students and staff died of typhoid and Rocky Mountain fever — a problem caused by bad water and sewer systems.

Two of the students, Peter Armell, 17, and Samuel Shem, 12, were buried in the Teller Institute Cemetery. Miss Lue H. Childs, a young teacher, also passed and her brother had her body shipped home to Chicago Junction, Ohio. This may have influenced Edith to pursue a nursing career later in life.

About 1903, after high school, Edith began work as an assistant to the Rev. Milton J. Hersey of the Episcopal Church at the Uintah Reservation, Fort Duchesne, Randlett, Utah. She described the condition of the hospital at Fort Duchesne as being extremely crude, with only one hospital ward for all patients. Men, women and children were all placed in the same room, sanitation was lacking, and Henry B. Lloyd M.D. was the only doctor at the fort. The hospital was understaffed and overworked.

After serving at Fort Duchesne for a few months, Edith made up her mind to attend nursing school in Portland, Ore., where she completed her courses at Good Samaritan Hospital in 1908. From 1909 to 1920 Edith served as a private duty nurse and then went back to Fort Duchesne to work until 1922.

Edith mentioned in her diary that she had a personal acquaintance with Chipeta, wife of Chief Ouray. She told the story of Chipeta coming to Fort Duchesne, nearly blind and Edith had helped to nurse her. She describes Chipeta as warm, friendly and cultured. In about 1921, a friend of Edith's from Grand Junction, William Weiser, came and took Chipeta to St. Mary's Hospital where surgery was performed on her eyes. It should be noted that William Weiser was the nephew of William Moyer, owner of the Fair Store.

Edith worked at San Francisco General Hospital and in Eugene, Ore., from 1922-25 and updated her nursing skills with each assignment.

Kate, Edith's mother, was not in the best of health, so in 1925 Edith returned to Fort Duchesne to be near her mother, who died in 1927. Edith stayed on at Fort Duchesne until 1930 when she accepted a position at the Yakima Sanitarium for Tubercular patients in Toppenish, Wash. As a nurse there she contracted the disease and from September 1930 to February 1933 she was on compensation leave while she regained her health. After that time she moved to the Haymond home in Salt Lake City.

In 1937, with Edith's health fully regained, she left Salt Lake City for an assignment to the Klamath Agency in Oregon, then to Warm Springs, Ore., then to Ponca City, Okla., at the White Eagle Pawnee Agency, where she worked until her retirement in 1950. She then returned to Salt Lake City to be with family, and her adopted sister, Vera Haymond.

While Edith never married, she did fall in love with a doctor, Eli Abraham Kusel of Oroville, Calif. She would vacation in Oroville and those were some of the happiest times of her life. Edith's love letters from 1942 and 1943 are in her files at the University of Utah. In her papers, many times Edith repeats that the greatest mistake of her life was she did not marry Eli, and he never married either. Eli died in 1947 in California, and left Edith a diamond ring as a remembrance of his love. He also left her a $1,000.

In Edith's diary where she kept her innermost thoughts are Frank Dean photos of the Ute Maiden, Captain Theodore Lemmon, and her mother, Kate. Also in the diary are the Delong Speech contest story at the Park Opera House in 1900, her love letters to and from Eli A. Kusel, and the love for the place she grew up — Grand Junction, Colo. This was her home.

Edith was very interested in furthering the cause of women in the workforce, helping some to gain an education, and sharing her talents. She was active in the retired Government Employees association, a native member of the Utah's Art Center, and a world traveler for the Business and Professional Women' Club. She went to places like Germany, Cuba and Hawaii, attending many national meetings for the club.

Edith was passionate about promoting the standards of Indian women in education, for which she received from the Department of Interior in 1950 an honor award, and once again in 1964, an award for meritorious service to the Indian Service.

It was said that Edith was a quiet person, regal looking in her smartly tailored clothing. She was remembered by her friends as one who always had a matching hat for each outfit, and when she spoke she commanded attention for her wisdom and understanding of situations, never speaking ill of anyone.

One of her many talents was decorating banquet tables for 20 to 300 people. Many organizations called upon her for their banquets; she would always tell them, "Oh, I have the right things in my attic for your particular theme." Her skill and arrangements were breathtaking.

Just before her death, Edith had broken her hip and was in St. Joseph Villa; the ladies of the Business and Professional Women's club would visit and ask if they could pick her up and take her to the women's lunches. Edith would say: "I don't believe I can go today, but soon we may be able to go out for lunch again"

That day never came. Edith Leroy Richardson died on March 16, 1977, in Salt Lake City. She had moved on to solve "The Great Mystery" as she called it. Edith was 95 years, 8 months old. The Little Ute Princess of Grand Junction was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in the Haymond Family Lot in Springville.

EPILOGUE

So if you're on Sixth and Rood some quiet morning where the old Grand Junction High school was, and you hear the sounds of a high-stepping horse team, a snap of a horse buggy whip, footsteps of two people — it just might be Capt. Theodore Lemmon bringing the Ute Maiden, WE-TA-LE-TA, Edith Leroy Richardson to high school for her lessons.

======================

Garry Brewer is storyteller of the tribe; finder of odd knowledge and uninteresting items; a bore to his grandchildren; a pain to his wife on spelling; but a locator of golden nuggets, truths and pearls of wisdom.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement